At RVTS, we are very proud of our Cultural Education team and all they accomplish in educating and mentoring our registrars about First Nations culture and the best practice provision of culturally-sensitive care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

Last year, we introduced you to RVTS Cultural Educator, Professor Marlene Drysdale (click here to read Marlene’s story).

Patrick Daley recently spoke with another member of the team, Glenda Humes, to learn about her fascinating life journey…and also learn more about her famous father!

Where did you spend your childhood?

I was born in Melbourne and spent some of my childhood there, but I largely grew up in Sydney.

My father is Gunditjmara from the Western Districts of Victoria, and my mother is Jawoyn – her mother was born in Pine Creek in the NT.

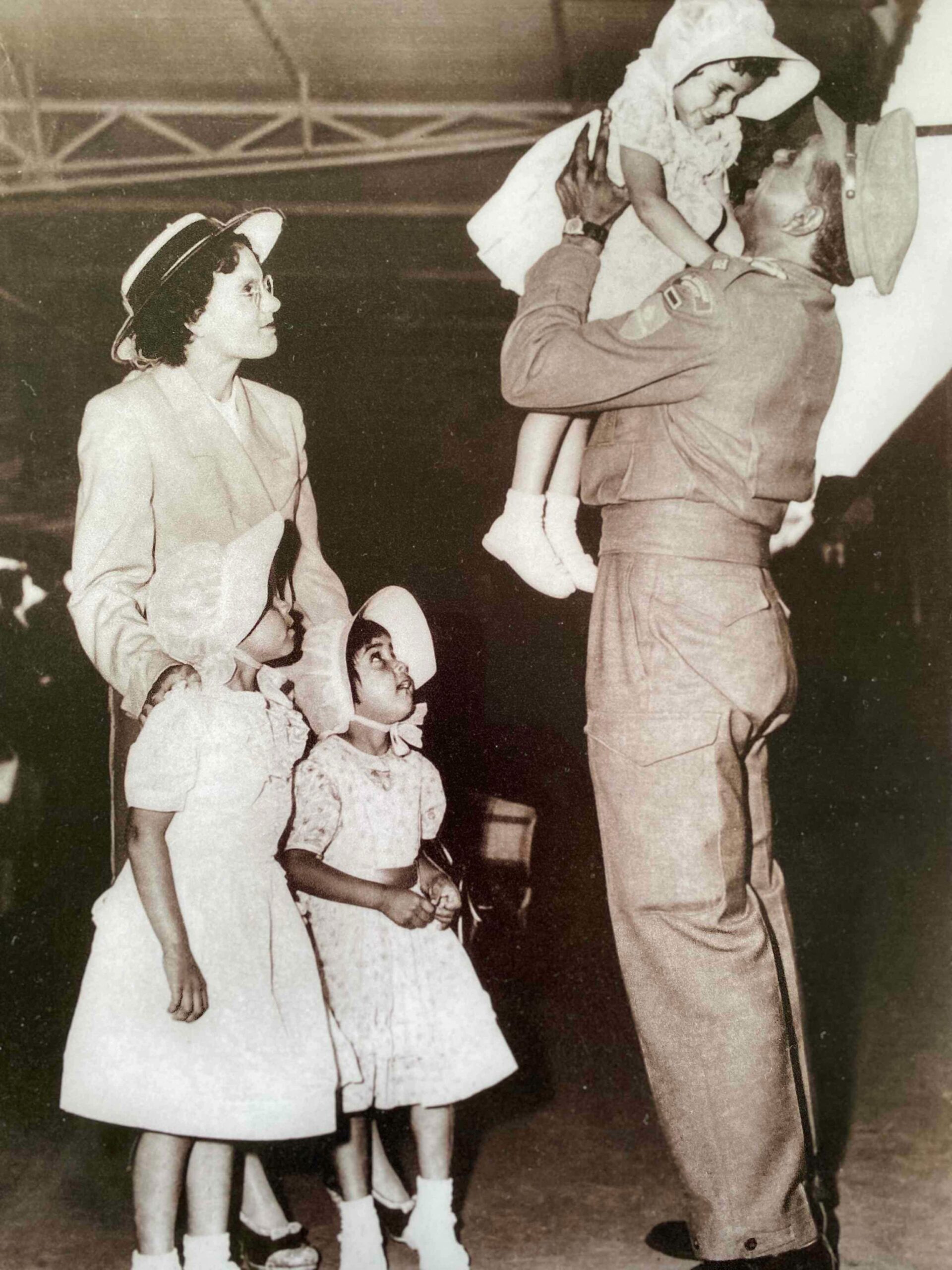

My father was Captain Reginald Saunders MBE – he served in the Australian Army during World War Two (serving in the Middle East, Greece, Crete and Papua New Guinea) and the Korean War in the 1950s.

I only found out later that he was well known. He was the first known Australian Aboriginal officer in World War Two, and Australia’s first Aboriginal commissioned officer at a time when we weren’t even counted in the census!

He fought in the famous Battle of 42nd Street, on Crete. After the battalion surrendered, he went on the run and hid on Crete for eleven months to avoid being taken as a prisoner of war. While in hiding, he was protected by a Cretan family and the village people in Lambini.

After the Korean War, my mother and father separated. We were a family of five daughters, so we moved to Sydney to be close to Mum’s family. We lived in a big housing commission area at Riverwood, in a former US Army hospital facility used during World War Two that was subsequently being used to accommodate hundreds of people waiting for government housing. When our turn arrived we moved to a house in Greenacre. I spent many happy years there.

My mother and father tried to get back together again in the 1950s, and we had a little brother as a result of that.

After the 1967 Referendum, my dad got a really good job with the Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs. He went on to have another four children.

Where did young adulthood take you?

I was married in 1966 – my husband Bill Humes, who hailed from a place called Wandering in WA, was also in the Army.

I had gone on to study a Bachelor of Laws and Masters in Indigenous Social Policy.

I did a lot of work in health and welfare for the NSW Government, then got a job in Canberra with the former Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) working to provide better services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

I lived with my father who was also in Canberra at the time. We had a great three years together before he passed. I travelled back to Sydney each weekend to see Bill and my children who were in their last years of high school.

On the eve of Australia Day in 1988, my oldest daughter, Alpena, died from an overdose. She was 21 years old. As a family we still went along to the events and the march on that day in her memory, as she was a real warrior for the rights of our people.

Bill also later moved down to Canberra, and we both had a year with my dad – they had lots of fun together. They were two country boys at heart…and they got up to lots of mischief!

Bill was like my dad – he was a good fella, and he had a good heart. He passed away 13 years ago.

What early experiences did you have regarding racism?

When we lived in Victoria, I can remember going to a pub in town after one of Dad’s football games. He was sitting at the bar talking to all his friends. I asked him how he knew so many people, and he said “It’s because I’m black”. It was the first time I’d thought about my colour.

I didn’t understand what racism was because everyone talked to Dad, but I know he suffered from racism when he worked on the tramways as a conductor after the War, and being racially abused. It wasn’t until later that I really got to understand what racism really was. There was a family next door to us in Riverwood who were a little bit racist to us. I got to understand what racism was and how it can hurt you.

Even in my 70s now, I still experience it – but it is more casual racism now. Things like people walking in front of you when you are waiting at the shop. But I don’t take that anymore – if I’m next in line and someone tries pushing in front of me, I’ll speak up. Equally, if someone else is in front of me, I’ll let everyone know that it is their turn next.

When Dad played football he was called a lot of derogatory names, even though they would add “But you know we love ya Reg!” I would also hear my nephews being called names like Midnight while playing footy and how accepted – but at the same time hurtful – these comments were, and how casual racism was and still is today.

That’s the reason we stick to our own mob, because it’s safe for us.

I didn’t realise Dad was famous until years later. I was sixteen years old and working as a telephonist in the Sydney telephone trunk exchange, and one woman came up to me and said “Is your dad Reg Saunders? He’s a very famous man!” I talked to my mum and she told me all about what he had achieved.

He’s got a room named after him at the Australian War Memorial; a teaching auditorium named after him at the Australian Defence Force Academy; a couple of streets named after him in Canberra; and a bridge in Portland, Victoria, not far from Lake Condah (Tae Rak) where he grew up.

But to me he was just Dad – he was always full of wisdom and an amazing man.

You’ve spent much of your career working in Aboriginal health…

Yes, I’ve always been interested in Aboriginal health.

I’ve served on the Board of the Winnunga Nimmityjah Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS) in Canberra; worked for NACCHO as their Deputy CEO and also served on their Board; and I was a Board member of the West Australian Community Controlled Heath Organisation.

I was also CEO of the South West Aboriginal Medical Service (SWAMS) in Bunbury. We did some amazing stuff there. The thing I am most proud of is that we were able to get ambulance membership for our people. Without membership it was $500 or $600 for an ambulance trip to hospital – it was causing a lot of our people to go into tremendous debt.

If you were a member of SWAMS, we would also pay for your medicines – this was before the gap was introduced. We realised that many of our people were trying to keep multiple balls in the air, including food and rent etc. We had even heard stories of people sharing their insulin.

The other thing I am really proud of is that we were able to train Aboriginal Health Workers in our clinic. That service is still going strong.

How did you become involved in RVTS?

Probably through Marlene Drysdale! I really liked the work she did.

I’m also a very cultural person. My grandchildren and many other young people call me Kabarli, which is the Noongar word for grandmother…it keeps up a part of the language of my grandchildren, which is really important.

What does your RVTS work entail?

I provide cultural mentoring to RVTS registrars, to help them better understand our culture and what First Nations patients need in accessing culturally supportive healthcare.

This includes ways to make a First Nations patient feel comfortable when coming into the clinic, enabling them to see a female doctor if they are a female, and having relatives accompany them to a medical appointment to ask questions on their behalf.

Those privacy laws are really quite a nuisance for us in this regard – they get in the way for us!

I talk with our registrars about our history, and all those social issues that impact on Closing the Gap. These doctors are probably getting a lot more education about First Nations people than most Australians would have received at school!

When I was growing up, all of the history we were taught was about the US and England – I learnt more about the US Civil War than our colonial wars here. So I always try to tell our registrars as much as I can.

We see the registrars four times a year, and sometimes I show them clips as it can be better than talking. For example, if I show them before and after photos of Juukan Gorge I don’t really have to say much. A lot of the overseas doctors who come from old cultures themselves really feel that and understand how important country is.

I’m not saying it is only Aboriginal people in Australia who feel country, though – when I was at Uluru once in my 30s, a non-Aboriginal woman came up to me and said “I had such an amazing experience there”, and I thought ‘Yeah, they feel the same as we do about this country – it’s not just about us’. I really had to think about that. The country speaks to all of us who want to hear it.

Has cultural awareness changed significantly in the past 20 years in the health sector?

Oh gosh yes, when you think how hospitals back then were treating First Nations people, they weren’t treated well.

It’s a lot different now, and there’s a lot more cultural awareness training – including how Aboriginal patients want to be addressed and how we can make health facilities a more welcoming place.

The current approach of encouraging Aboriginal people and those from multicultural backgrounds to become health professionals is also going to lead to big improvements down the track.

It’s also important to realise that not all Aboriginal people want to go to an AMS. Now that most clinics can do Aboriginal Health Checks, it gives Aboriginal people more choice about where they access healthcare.

Photo above: Hilary Saunders and Glenda Humes with the water tower in Heywood, Victoria, depicting the image of their father Captain Reginald Saunders MBE. (Read more here).

You are putting your Bachelor of Laws to good use now in Toowoomba…

Yes I am! I serve as a Board member of the Aboriginal Family Legal Service and I am involved with Murri Court, which is an alternative sentencing process for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders charged with less serious crimes.

The person will come before the Magistrate’s court first, and if they plead guilty they can opt to come before the Murri Court for sentencing.

Murri Court comprises an Elder or respected person and the Magistrate. We sit on the other side of the table (not on the Bench) and we have the defendant, lawyer, police prosecutor (who is not in uniform), probation officer and other support group representatives.

It is very casual – families come in, we tell jokes, we laugh and we cry. It’s very powerful.

After we’ve heard their stories, we can say “You’ve got some really big anger management issues, or suicidal thoughts, or drug and alcohol problems – would you like to get some counselling and speak to someone?”

A lot of Aboriginal people don’t think they will like counselling, but once they experience it a lot of them are really for it. Some even tell their relatives “You should get counselling too!”

They have to do a counselling or rehabilitation program for at least three months, and then we sentence them. We try to ensure they won’t have any more business with the court, and we offer them continuing counselling or support.

We don’t have a lot of re-offenders, and we’ve been so successful that we are talking with the Magistrate about having a similar thing for younger offenders in Toowoomba.

If we can change their lives we will change future generations as well – it’s a long-term thing.

You are ‘retired’ but you seem very busy – researching your Dad’s military history and doing lots of volunteer work, including with Lifeline, the local hospital and school – as well as raising teenage grandchildren!

Yes! I have three children and nine grandchildren. I have one grand-daughter who has almost completed her Bachelor of Environmental Science, three grandsons (one in Year 11 and two in Year 10), a grand-daughter who has just finished Year 12 and is doing legal studies, and a son with a Degree in Social Science working in WA in financial counselling.

It has been a real delight raising five of my grandchildren.

Someone once said to me “They keep you young” – which is true – but they also keep you tired!

But it is a real joy to be around young people, I have loved every minute of it.

Read more about Captain Reginald Saunders MBE here.

Hear Glenda speak about her father and the Battle of 42nd Street here.