Professor Marlene Drysdale is a champion of cultural awareness – and her work at RVTS is critical in shaping a health system that is culturally safe and welcoming for First Nations people, now and into the future.

Patrick Daley chatted with Marlene recently about her own remarkable life journey, and why RVTS registrars (and their communities) gain so much from the cultural awareness training developed by our Cultural Education team.

Tell me a little about your childhood…

Photos from top: Marlene as a baby and then a toddler (in her grandfather’s yard); and Marlene’s father, Archie (Rocky) Jones.

I was born in Melbourne on Wurundjeri country, but lived most of my childhood in Echuca on Yorta Yorta country.

My father was an Aboriginal man, and my mother was from English descent. My father was a wonderful and gentle man. He fought in World War 2 and returned to Australia but there was no military decoration for him – and no land either, of course.

I did my early schooling in Echuca, and until I was about ten we lived in tents on the riverbank. It was a tough existence, but the old saying “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” is very true.

One thing that did shape my life there was befriending an old lady who had a beautiful garden – I’d stop by her house each morning, and she would tell me all sorts of things about her flowers. Then I’d tootle off to school.

She ended up employing me on the weekends to do some weeding. I’d get sixpence – I was pretty cheap labour in those days – but she taught me to spell and made me spell the names of the plants.

I found out later that she was a retired teacher and was adamant about me going to school. She cut my lunch and put it in the letterbox each day for two years – it was easier for me to pick up lunch and go to school than face her on a Saturday morning with an explanation! So I owe her a lot and she really shaped my life.

What happened after you left school?

I really wanted to do law, but left school when I was 14.

I got a job as a secretary trainee at a legal aid office, but realised I had to go back to school in order to get to university.

So I did that, then got a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Tasmania with a double major in politics and management. At the same time, I studied a Bachelor of Arts in Aboriginal Studies at the University of South Australia. This set me up for the rest of my life.

In amongst having a family and work, I also did a Masters of Education with a specialty in Aboriginal Education. Then I got a PhD for my thesis, Aboriginal women and reconciliation in Australia: Communication strategies and symbolism. Those were busy days!

What were your early experiences in cultural safety and cultural awareness?

When I was a kid there was no focus on Aboriginal health. The health conditions I have now are a product of poor housing, and living in a tent when it was wet and horrible.

We were seen as discarded citizens and it was tough as a kid. I saw my father come home from being picked up by the police and bashed – once he had a broken jaw that was wired up for months – and I saw our house turned upside down several times.

As a child, I knew we were not part of the community nor the decision-making process, so I wanted to work in a space where you can have some influence. I always thought that if you can make one per cent change and everyone else does that too then you can make change – but it has been a tough road.

Is the approach to Aboriginal healthcare better now, or just tokenistic?

It’s mixed. I see some remote areas that do it really well and some that are still a long way down the track.

You’ve got to engage the local Aboriginal community, you can’t have a top down approach – that mission mentality of “We’ll make the decisions for you and you’ll just do it” doesn’t work. Aboriginal people know what they need for their communities – you just need to talk to them.

Unfortunately, institutional racism is still alive and well – it’s subtle, but it’s there – including in the health sector.

I must say an exemption has been RVTS – they have really walked the talk and I love working here. They have included Aboriginal Health in their training curricula, and have insisted their registrars and staff are trained in cultural awareness and safety.

How did you get involved with RVTS?

Aboriginal health has always been a passion, but I could never be a doctor or nurse – I can’t stand the sight of blood, especially mine. I had been working in education in the first part of my career, so combining education and health was the perfect mix.

I was Head of the Aboriginal Studies Unit at Monash University for fifteen years before setting up and leading the Indigenous Health Unit (as part of Monash’s School of Rural Health) for ten years. While I was working there, I saw there was an opportunity to train doctors in cultural awareness. I co-wrote the curriculum with a colleague and had huge interest from students. This led to my initial work with RVTS, coordinating their cultural awareness webinars and cultural mentors.

What does the cultural awareness process involve?

It’s about ensuring that our future doctors understand the past history of Aboriginal Australia, and the Aboriginal culture.

The past is critical to Aboriginal people. We have strong connections to the past, to the land, to spirituality and to family – we bring those connections forward to each day and whatever life throws at us…so the spiritual aspect of Aboriginal health is really important.

How does that factor into Aboriginal healthcare?

It’s about recognising that there’s not one sort of medicine – the biomedical model of medicine is not the only way. There is Chinese medicine and we have Aboriginal medicine too.

The other important element for Aboriginal people is being able to access the ACCHOs – because there we don’t have to constantly justify the past, we don’t have to justify our spirituality and we don’t even have to justify ourselves – we are known and understood there.

With ‘six minute medicine’ you are constantly repeating your story. People don’t understand it, and everyone is busy and doesn’t want to listen.

Listening to Aboriginal people is the key to understanding us and where we come from.

We can read body language like anything – we know if someone is interested in us or not. If you come to a doctor and they are typing into a computer while you are talking to them, an Aboriginal person will just walk out of the surgery.

These are the type of things you need to educate registrars about.

How do you deal with blatant racism?

In my various roles, I have had registrars who find honest colonisation history very confronting and don’t handle it well, but the facts are there and you can’t dispute them – it’s up to them to get onboard.

Some registrars can be dismissive of Aboriginal history, too – “It happened years ago, get over it” – but I remind them we haven’t got over the holocaust, we don’t get over ANZAC Day, and if one of your family has passed away you don’t forget them. Sometimes just bringing the registrar back to reality is all that is needed.

Other registrars find it hard to call out racism – but I tell them that if someone makes a racist joke, the most powerful thing you can say to those around them is ‘I don’t agree with their point of view and I’ll leave the room till they finish’.

We also have to keep reminding health services that when they say “Aboriginal patients don’t turn up for their appointments and they don’t take their medicines” it may be because they haven’t got any transport or any money. There’s no excuse for ignorance these days!

Tell me about unconscious bias…

People don’t like being out of their comfort zone. We have just developed a unit on racism and unconscious bias, and some people find it very difficult to realise they have biases within themselves.

Unconscious bias is the greatest enemy in the medical system. As a doctor, you need to see your patients in an unbiased way.

Some doctors say to me that they treat everyone the same, and I say to them ‘Well, you should be treating them as individuals’. If you had a patient walk through your door with a burqa, and a person with a pair of shorts, thongs and a singlet, would you treat them the same?

Understanding privilege is a really big thing too. I’ve had people say to me “You’re alright, you’ve got a nice house”, and I say to them “How do you know it’s my house, and I’m not just staying there with someone?” They’re making assumptions.

The other big one people say to me is “You don’t look Aboriginal” – to which I say “You don’t look racist”.

Or “I don’t have any Aboriginal people in my community” – to which I say “How do you know?”

You just have to keep battling away at it, that’s the way it is!

What moments have caused you to take heart?

Sometimes when I’ve been teaching cultural awareness, it has been very heartening to watch a peer group interacting on these issues, because often a peer will call out a fellow registrar without me even having to.

And a few years ago I got to know a young doctor from Iran who’d struggled with English. When he passed his medical exams I was the first person he rang. He said “I called you before I rang my mum!” That was wonderful and I’m still in contact with him.

It’s also a wonderful feeling of accomplishment when you have a registrar who isn’t keen to do any cultural awareness, but a few years later says to me “Thank goodness you taught me about that in my registrar years – I didn’t realise then what it meant but I do now”.

How has RVTS been innovative in the cultural awareness space?

Engaging cultural mentors for each RVTS registrar has been a fantastic initiative – it enables the registrar to talk with them about the cultural and spiritual things, connect with others in the community, and better understand the protocols of Aboriginal culture – for example, places where males may not be able to visit. All of this is really critical.

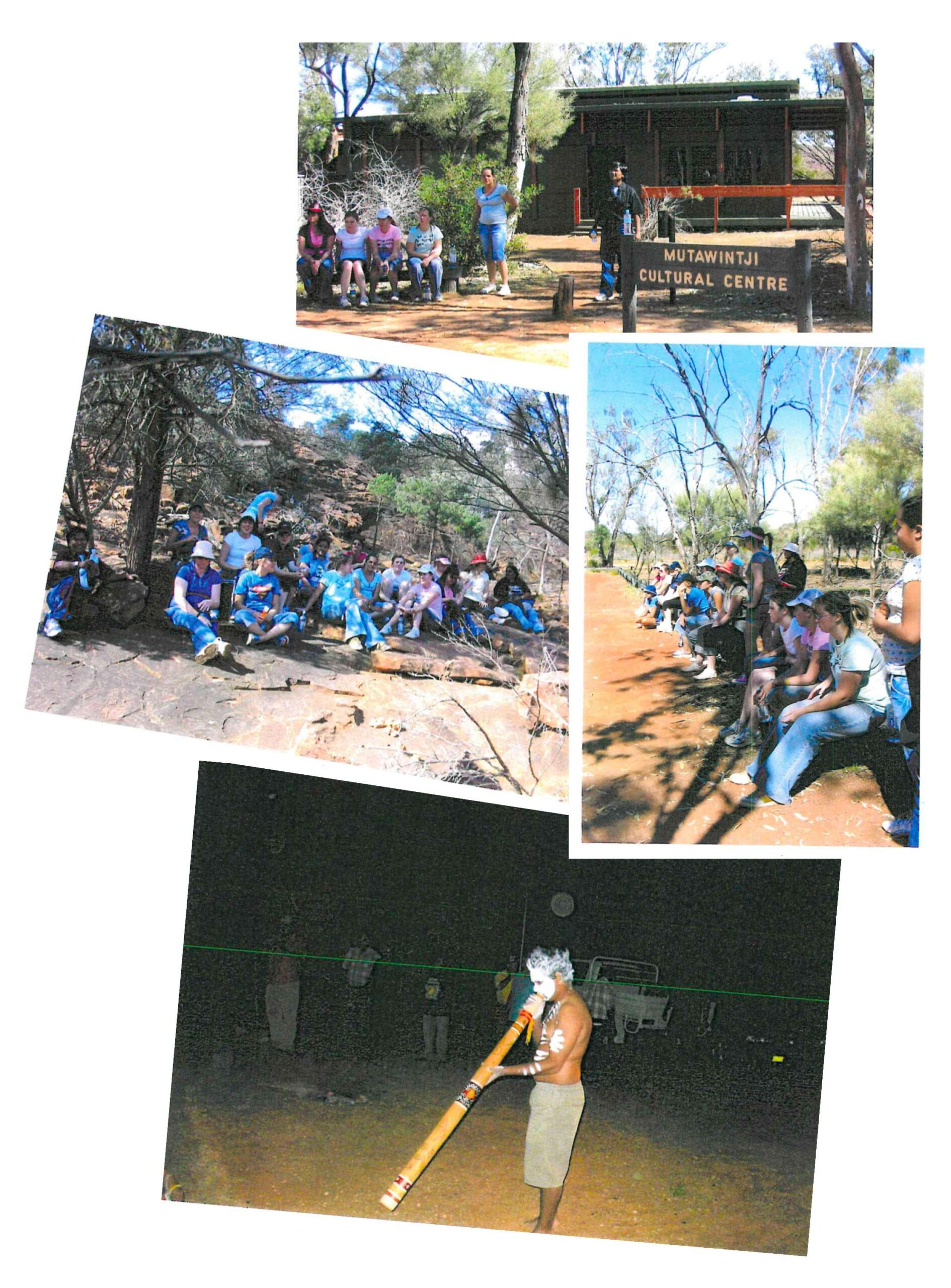

Another success story over the years has been taking doctors and nurses out on country on cultural immersions – they get the chance to camp, eat, chat and have honest conversations with an Aboriginal community, and that changes attitudes. I still hear from participants as to what a difference that has made in their approach to healthcare.

Tell me about “You can’t ask that!”

As part of our cultural awareness program at RVTS, we run peer-to-peer sessions – both face-to-face and via webinar. One exercise we’ve introduced at these sessions has been “You can’t ask that!”

We put slips of paper with topics on the table, and the participants have to read out whatever they pick up.

The topics include things like “Why do Aboriginal people get free housing?”, “How much Aboriginal are you?”, “Why don’t Aboriginal people take their medicine?”, “Why don’t Aboriginal people come to the clinic?”, “Why does everyone want to go to the clinic with the patient?” and “I don’t think Aboriginal people should be making decisions for certain things”.

We have received great feedback from the registrars because these are the type of questions they don’t usually get to talk about.

In all my sessions, I say to the group “There are things you may not agree with or feel challenged about – I want you to understand that you are not responsible for what has happened in the past but you are responsible for what happens in the future.”

Knowing what you know now, what would you tell your younger self?

Never give up. There’ll be tough moments along the way, but if you yield to the pressure then you’ll never get there, you’ve just got to keep going. I mean I’ve retired three times, but something will come up and annoy me and I’ll say “They can’t get away with that!” so I get back to work again. You’ve got to keep up the fight.

In addition to her RVTS role, Professor Marlene Drysdale is also the Senior Aboriginal Health Advisor for Eastern Victoria GP Training. Prior to that, she worked as the Senior Aboriginal Advisor for the Federal Department of Health and with General Practice Education and Training in Canberra.

Marlene also worked for several years in Cambodia as a Director for Developing Cambodia by Degrees, and was awarded the position of Adjunct Professor for the Asian Institute for Health Sciences in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 2014. She has received many awards for her commitment to education, Aboriginal health and governance.